One of the givens in heading out on a road trip is that there will be, you know, roads.

When on July 7, 1919, a young Dwight D. Eisenhower and 300 other men set forth in 81 Army vehicles and trailers to motor from Washington, D.C., to San Francisco, there was no reasonable expectation that the transcontinental adventure would go smoothly. It would not go smoothly, in the literal sense, because there was almost no pavement between Illinois and the Pacific Ocean.

The Motor Transport Corps’ 3,000-mile trip would proceed over paths that in many places were so crudely constructed or maintained that to call them roads would be like referring to a gardener’s trowel as a snowplow.

During the two-month drive, which bounced and burped along at an average pace of 5.67 miles per hour, the convoy experienced 230 road incidents such as breakdowns, accidents and extrications. Nine vehicles failed to fully cover the route, along which soldiers had to repair or replace wooden bridges (14 in Wyoming alone) that could not handle the vehicles’ size. One of the trucks, loaded with a tractor, weighed more than 10 tons.

That historic convoy left a lasting impression on Eisenhower, who when he was president 37 years later authorized the country’s interstate highway system. The route that he traversed in 1919 was at the time called the Lincoln Highway and is closely aligned with today’s Interstate 80.

Carl Fisher, who in 1909 founded the Indianapolis Motor Speedway that to this day continues to host the annual Indianapolis 500 automobile race, in 1912 had an even bigger idea: He proposed that a “Coast-to-Coast Rock Highway” be constructed from Times Square in New York City all the way to the site of the 1915 Panama-Pacific Exposition in San Francisco. He projected the cost to be $10 million, which would be raised through public and private means.

Henry Ford declined to support the endeavor, however, giving as his official reason that the public would never agree to fund good roads if he and other automakers did it for them.

Nevertheless, Fisher received backing from a number of auto-industry executives, including Henry Joy of the Packard Motor Car Company. It was Joy’s idea to call the road the Lincoln Highway, which in 1913 “was officially incorporated as the Lincoln Highway Association,” according to the LHA website.

Progress in completing the project was slowed not just by financial concerns, but also by spats over what path it should follow. The governors of Colorado and Kansas, for example, had been assured that the Lincoln Highway would go through their states. Ultimately, it did not. In Utah and Nevada, there were competing camps on whether the road would go through or skirt below the salt desert directly west of Salt Lake City. Delays and ill will resulted.

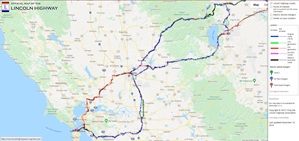

As shown on the accompanying map, the original Lincoln Highway diverged and followed two paths through parts of Nevada and Northern California. More or less, one of those two paths corresponds with today’s Interstate 80, and the other lines up with contemporary U.S. Route 50.

World War I, in which the United States fought for 19 months before the horrific conflict ended in November 1918, was a major distraction in terms of the Lincoln Highway’s advancement and construction. The war did, however, speed up the development of mechanized transport in a century that came to be dominated by the automobile – at least in this country.

Through the mid-1920s, work on the Lincoln Highway continued under the LHA while hundreds of other highways were built in other parts of the country. They were of vastly varying lengths, quality and purposefulness. They tended to be given names, along the lines of the Lincoln Highway, and “were primarily marked by painted colored bands on telephone poles,” the LHA website recounts.

The Lincoln Highway lost much of its mystique in 1925 when the American Association of State Highway Officials (AASHO) launched a federal highway plan. Major roadways were to be designated in an orderly way by numbers: east-west routes in multiples of 10 (e.g., U.S. Highway 50) and north-south routes ending in 1 or 5 (e.g., U.S. Highway 101).

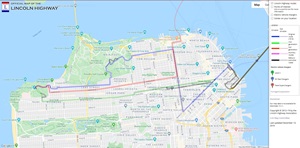

Hobbyists’ fascination with the Lincoln Highway has endured to this day, however. The LHA, which had gone dormant by the ‘50s, reactivated in 1992. (Thank the World Wide Web for that.) LHA has chapters in 12 states, including California. The organization’s website includes an interactive map of the United States that indicates and allows visitors to zoom in on the 1913 original route, two subsequent generations of routes, auxiliary routes and detours. (See the screen shot image that accompanies this article.)

The site also provides pictures and descriptions of places along the Lincoln Highway that have survived to this day and can be visited. There are many contemporary roadways in Northern California that have been paved (and repaved, sometimes by Caltrans!) over original stretches of the route that Eisenhower and others traversed more than a century ago.

On a sunny weekday in January, CT News ventured out to the extreme western point of the Lincoln Highway, a few hundred feet from the Legion of Honor in San Francisco. A plaque and weathered concrete marker, which includes a small bust of President Abraham Lincoln, can be found there next to a bus top. Boy Scouts installed hundreds of the markers along the entire route, back in 1928.

It’s a pretty setting and a pleasant place to reminisce on how the nation’s transportation system has evolved over the past century. And if you’re there during normal business hours, you can stroll over to the Legion of Honor and grab a bite to eat, too.