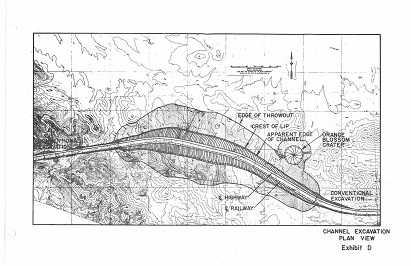

The 1963 Project Carryall Feasibility Study’s exhibits include this terrain map that pinpoints the project’s location, 11 miles north of the small town of Amboy.

Note: This is the third in an occasional series of CT News stories that explore the century-plus history of the Department and California’s highway system.

Bulldozers, graders, asphalt mixers, rollers – folks at the Division of Highways (now known as Caltrans) relied upon strong-arm tactics to tame the terrain and construct California’s roadways.

One thing they did not resort to using, of course, was a nuclear bomb.

But they almost did. Twenty-two nuclear bombs, as a matter of fact.

No, this isn’t April Fools’ Day, nor has CT News been taken over by Mad Magazine or The Onion. The story is a true tale from the past, though thankfully not a blast from the past.

In 1963, the Division of Highways teamed up with the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission and the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway Company to envision “Project Carryall.” The three partners produced a 78-page (not including maps and appendices) feasibility study about creating a two-mile ditch in a Mojave Desert mountain range by means of a “nuclear excavation.”

What was their incentive? For the road planners, it would mean shaving 10 miles off the future Interstate 40 stretch between Bishop and Needles. For the railroad company, it would mean reducing freight travel time by 50 minutes via a more-direct, less-hilly route. For the bomb bunch, it would play into the grand idea of using nuclear weapons for peaceful purposes, a chipper concept formally known as Project Plowshare and that resulted in 31 nuclear explosions (in Nevada, New Mexico and Colorado) from 1961 to 1973.

A model of Project Carryall shows how planners envisioned the “nuclear excavation” road and rail project through the Mojave Desert. The crater at lower right is for Orange Blossom Wash runoff storage; it would be created by a 100-kiloton bomb.

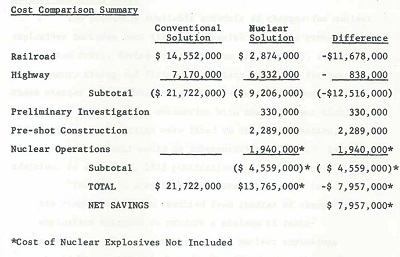

The Division of Highways already had considered tunneling through the Mojave’s Bristol Mountains, but that approach was deemed too costly, at $21.7 million. The less-subtle Project Carryall, however, with its synchronized sprinkling of 20-kiloton to 200-kiloton bombs, would follow roughly the same path and was estimated to cost almost $8 million less. Which is kind of misleading since the estimate did not include assembling and transporting the nuclear devices, costs that presumably would be borne (and never disclosed) by the U.S. government.

Penny-pinching didn’t entirely rule Project Carryall. As its feasibility study states, “The most economical solution would be to excavate the entire channel with one detonation [i.e., all 22 bombs would go off at the same time].” However, the agreed-upon two equal detonations spaced a few months apart would have several benefits, including this nerdy nod to Atomic Age enthusiasts:

“The ability of existing emplacement holes to hold their integrity in the vicinity of the detonation is of considerable interest.”

In other words, would the good work of one bunch of bombs be compromised by the good work of a subsequent bunch of bombs? Inquiring minds wanted to know! Perhaps you can begin to see why the project’s excitement level rose to include calls for having half the nuclear fireworks explode on the Fourth of July, and why officials already were jockeying for the best seats on an imagined viewing platform.

What a show (two shows, in fact) it would be. The strategically placed 22 underground blasts would result in a chain of connected craters with a width of 600 to 1,300 feet and a maximum depth of 360 feet. (Conventional excavation methods could go no deeper than 100 feet, it was said at the time.) Yes, there would be a proverbial mushroom cloud 12,000 feet high and seven miles in diameter, but assuming the weather cooperated, the feasibility study’s authors reassured, no serious fallout would occur beyond five miles.

As for the 150 residents of Amboy, 11 miles to the south, it probably would be prudent for them to evacuate during the nuclear excavation. The Project Carryall feasibility study determined that the resultant air blast “would not be expected to cause damage” in Amboy, but the ground shock would make it “possible that minor damage, such as cracked plaster, might occur.” No mention was made of the five residents of Bagdad, nine miles from the project’s site, nor of any desert animal or plant life whatsoever.

As for highway and roadway construction, the study says work would begin “as soon after detonation as possible.” How soon? “Entry for an eight-hour work day or 40-hour work week without unusual safeguards would be possible within about four days.” Road crews ultimately would construct four lanes of freeway, leaving room to add four more lanes should the need arise.

Alas, the feasibility study did identify a few potential glitches. An existing Southern California Gas Company pipeline snaked to within two and a half miles of the blast zone, which created some anxiety. More troubling was that “the nuclear design alignment has one large drainage problem,” at Orange Blossom Wash. Rare, heavy desert rainstorms could cause sudden flooding, unless … Hey! Let’s stick with the plan and just add a 23rd nuclear bomb to the project.

The feasibility study presented cost estimates with an asterisk that has more impact than, say, the “batteries not included” asterisk on child’s toy boxes

“The most economical solution appears to be a crater which will accept the maximum possible flood expected in Orange Blossom Wash,” the feasibility study asserts. A 100-kiloton explosion would create an 870-foot-wide, 250-foot-deep bowl. “The water stored in this crater would be available for common usage in the area.” The spirit of sustainability, circa the early Sixties.

Blasé yet bone-chilling phrases are scattered throughout the feasibility study, including depth-of-burst, multiple-charge cratering, neutron absorbing materials, peak surface velocities, “prompt” fallout, tropospheric refraction and – droll alert – potentially damaging. The study concludes by saying, “This project is deemed to be technically feasible.”

Ultimately, however, Project Carryall proved to be politically unpalatable. The idea that was launched during John F. Kennedy’s presidency stalled under his successor, Lyndon Baines Johnson, who became enmeshed in issues such as civil rights, the Vietnam War and urban rioting. The 23 nuclear blasts that were proposed to be conducted in 1966, and the freeway opening on July 1, 1969, did not occur. (Interstate 40 opened in 1973.) Project Carryall ended with a whimper, not with a bang. Or rather, not with a KABOOM! KABOOM!

Project Plowshare petered out, too. Nuclear excavation in the desert wasn’t its only scrapped plan. There was no fission expedition to create a Panama Canal alternative in Nicaragua, no atomic explosion to form a harbor in Alaska, no underground obliteration to link aquifers in Arizona.

In 1984, when Los Angeles Times reporter Mark A. Stein asked Caltrans spokesman William McKinney about Project Carryall, his response reflected an enlightened outlook about the pragmatism of peaceful nukes.

“The whole thing sounds very naïve,” McKinney said. “They talked about breaking a few windows in Amboy. Well, Amboy is only about 10 miles away – it would have wiped Amboy off the map. And the fallout. They predicted it would have been contained within five miles of the blast site, but really it probably would have been blown all the way to the East Coast.”

Another Caltrans spokesperson at the time, Tom Smith, told the Times, “We were innocent way back then, and had nothing but visions of peace forever in our heads.”

Are you curious about some aspect of Caltrans’ history that you think would make a good candidate for this series? Please email your idea(s) to Reed.Parsell@dot.ca.gov.