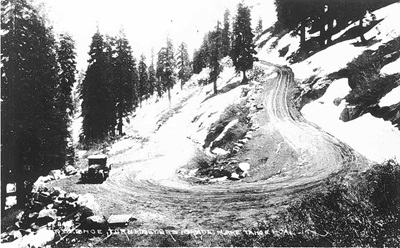

This undated photograph of the old wagon trail that eventually became U.S. Highway 50 was taken at Horseshoe Bend.

Note: This is the second in an occasional series of CT News stories that explore the century-plus history of the department and California’s highway system.

What was our first state highway? Like so many California stories, this one begins Jan. 24, 1848, in them thar hills.

The Gold Rush that followed James W. Marshall’s finding of sparkly flecks in Coloma posed transportation challenges for Easterners, Europeans and others who wanted in on the action. Sailing around Cape Horn took up to eight months, and primitive overland routes had their issues, too. (Cue the Donner Party tale.)

The overland route to Placerville, the hub of early Gold Rush activity, entailed laboring over Carson Pass on the Mormon Emigrant Trail. A more-direct route from northern Nevada was initiated in 1852. It skirted Lake Tahoe’s southern shore and reached Placerville via Echo Summit and became known as Johnson’s Cutoff. Bids to make it a public wagon road, rather than a string of toll-imposed paths through private properties, fizzled.

Before the fizzle, state Sen. Sherman Day prepared for the Legislature a document titled “Road Across the Sierra Nevada,” in 1855. In it, he called population growth the state’s most urgent demand” but did not distinguish himself when he opined which immigrants were desired and which, ahem, were not.

“We need … the farmers and free laborers of the Western States, who bring with them their wives and their little ones, their flocks and herds of cattle.” The permanent residence of what Day called “the Asiatic race,” however, “is certainly not to be coveted.” Sadly, such prejudice against Chinese laborers was widely shared, including by California’s third governor (1852-56), John Bigler, who enacted anti-Chinese “coolie” laws.

Cultural attitudes may have been backward but the quest for a good mountain-crossing road proceeded inexorably forward. According to the June 13, 1868, edition of the American Journal of Mining, El Dorado and Sacramento counties in 1858 each pitched in $25,000 to build a wagon road between Placerville and Nevada. Private enterprise took over in 1860 and completed the task three years later – as it turned out not a moment too soon.

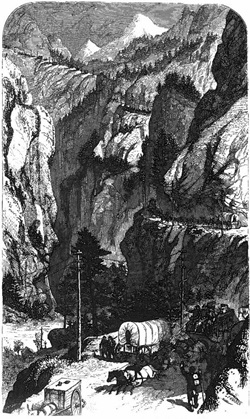

Gold Rush fever had pretty much petered out by the mid-1850s, but prospectors’ heartbeats rushed anew when the Comstock Lode came to light in 1859. Suddenly crossing the Sierra Nevada became a hot ticket, and toll-takers along the route collected tens of thousands of dollars annually for several years. According to a California Highways and Public Works (Caltrans’ predecessor) document from 1942, the wagon road was traversed in 1862 by 30,000 tons of freight and 36,500 passengers.

A PG&E Progress story from 1966 paints a vibrant picture of the then-century-ago scene.

In 1865, crossing the Sierra Nevada in a wagon was one tough task. Four years later, the transcontinental railroad’s arrival changed things.

“From 1859 to 1866, this route was the scene of one of the greatest processions of horse-drawn vehicles known to man. Wagons so jammed the road that if a driver dropped out of the traffic he had to wait until dark to get back in.” Even the short-lived Pony Express galloped along this trail.

“Although other routes have lower passes and easier grades, no other can compete with this for the ordinary purposes of wagon travel,” the American Journal of Mining reported in 1868, “because this is on the shortest route between Sacramento and Virginia City, is an excellent road, and is kept in fine condition.”

Toll collections peaked at $190,000 in 1863. By 1865, at least 50 restaurants and other businesses lined the route. As Comstock silver fever cooled and the transcontinental railroad arrived in 1869, however, and the economy sank, the wagon trail gathered dust – proverbial in addition to the normal kind.

Meanwhile, and starting as early as 1791, believe it or not, a bunch of Europeans and a few New Worlders worked on developing the internal combustion engine. (Henry Ford built his first automobile in 1886.) As transportation technology evolved and the American West was wrapping up a wild, wild 19th century, California established the Bureau of Highways in 1895. On Feb. 28, 1896, El Dorado County deeded the “Lake Tahoe Wagon Road” to the state, and the state highway system was born.

In 1899, the state set aside $5,000 for the road to be surveyed and $20,000 for repairs, improvements and structures. On Nov. 1, 1900, El Dorado County Commissioner Marco Varozza presented an update to Gov. Henry T. Gage that included this overview:

“The Lake Tahoe Wagon Road, which is entirely situated in El Dorado County, commencing at the junction of the Newtown and Placerville roads, a short distance easterly from Smith’s Flat, has its terminus at a point on the east boundary line of the State of California, at or near Lake Tahoe, traversing about 58 miles of mountainous country. Owing to the character of the country traversed, a great amount of repair work is found to be necessary to keep the road open to travel, and it has been the intention of your Commissioner to make all improvements as lasting as possible.”

The trail’s first major paving was in 1923, it became part of Highway 50 in 1926, and it’s been all up and down hills ever since.

Are you curious about some aspect of Caltrans’ history that you think would make a good candidate for this series? Please email your idea(s) to Reed.Parsell@dot.ca.gov.