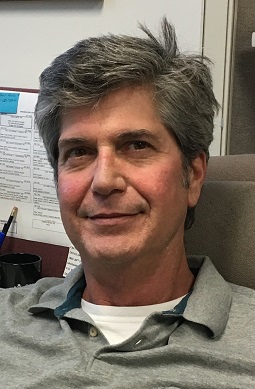

Erol Kaslan: Hello, greater sense of purpose

Thirty autumns ago, Erol Kaslan directed contractors as they shored up the destroyed Cypress structure so that rescue and recovery operations could proceed.

The associate bridge engineer issued orders, but in a way received one, too.

“It was my experiences at Loma Prieta that changed my career direction,” Kaslan, 59, now Chief of Structure Investigations – North, explained recently in his Sacramento office. In 1988, he joined the department as a bridge design engineer. By October 1989 he was on his bridge construction rotation assignment in Richmond.

“After the earthquake, I didn’t feel compelled to go back to bridge design,” Kaslan said. “I wanted to stay as a field engineer. I felt that it was better suited for my personality and … I also had a lot of thoughts about bridge design, having seen a monumental structure laying in rubble.”

Kaslan was born and raised in the East Bay and earned his master’s in civil engineering at UC Berkeley. When he arrived at Cypress the day after the earthquake, he was “amazed, almost angry” that it had happened.

He and colleague Rob Salaber walked around the site to assess damage.

“I noticed that there were some DOAs,” Kaslan tells Jim Bush in his Loma Prieta Oral history interview from Nov. 13, 1989. “D-O-A were spray-painted on the sides of the columns, which made it real apparent that there were dead people in the structure. I mean, you’re not really acquainted with dead people in day-in-and day-out life and, ah, I don’t know. I was just becoming overwhelmed.

“I really felt that I had a sense of duty. I really felt that I had to do something.”

"Had seen it on the news all night long, of course, and seeing it in real life there, you could look through the deck and see water under the Bay Bridge. Just shocking. Really shocking."

Prior to going to Cypress, Kaslan and Salaber went to the damaged portion of the Bay Bridge.

We “really couldn’t believe our eyes what had happened,” Kaslan says in the 44-minute interview. “Had seen it on the news all night long, of course, and seeing it in real life there, you could look through the deck and see water under the Bay Bridge. Just shocking. Really shocking.

“We weren’t smiling, we weren’t laughing. We were, you know, I don’t want to say serious or grim, but that was what it was. There was nothing funny here. It was just amazing, but we were definitely going through an experience. Exhilaration. An exhilarating experience.”

Exhilaration gave way to initiative at Cypress, Kaslan says in the old tape. “Really had to pull everything that I ever learned in school and in the field together and also reach down inside of me and pull up a lot of self-confidence just to make a decision and not worry about it, knowing that I was doing the right thing.”

Adding to the pressure was the presence of journalists.

“Rob and I looked at each other and really realized that this was a circus,” Kaslan says about the scene Wednesday afternoon, less than 24 hours after the earthquake. “The press were about a block away. They had set up a press gallery, and all ears, eyes, shotgun, microphones, dishes, telephoto lenses were all focused on us. We really felt like we were a spectacle to be watched here.”

“There were reporters all over the place, hassling the hell out of us,” is how Salaber puts it in his Loma Prieta Oral History interview.

Kaslan witnessed the rescue of Buck Helm some four days after the Cypress had collapsed around Helm’s car. Kaslan is even a blurry presence in a front-page San Jose Mercury News photo that chronicled the event.

“Everybody kind of came together for that thing,” he recalled in late May. “When they extracted him, when they finally got him out … he was alive, and it was really pretty cool. We all felt wonderful. Cold, rainy morning, that morning, and no one felt a thing.”

Soon after, Kaslan transferred to the Division of Maintenance and by the mid-1990s became a senior engineer. For eight or nine years he was an engineer diver, and served as a fracture critical engineer for a while. “It’s all been field, structural evaluation,” he said.

Kaslan and his wife, Cat, live in Roseville. They have three children: Aaron, 38, Camille, 27; and Nate, 22.

Thirty-one years into his Caltrans career, Kaslan remains intensely motivated by what happened in Oakland on Oct. 17, 1989.

“In my career and my profession, I am committed to see that not happen again,” he said. “Not on my watch. That’s deep inside. That’s an emotional drive.

“Maybe one of the reasons why I feel like I’ve had a rewarding career is that I have a good purpose here. I have defined my purpose, and I am comfortable with my purpose, and I am passionate about that. And I can easily relay that to anybody that talks about it.”