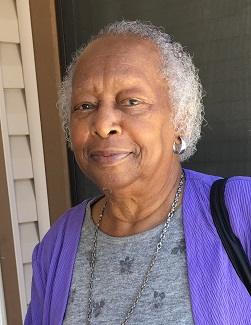

Algerine McCray: CT reaches out to the community

After the Loma Prieta earthquake so dramatically destroyed the Cypress Street Viaduct in Oakland, Caltrans embarked on a lengthy project to fortify the State Highway System’s bridges.

Meanwhile, Caltrans executive Algerine McCray set about strengthening the department’s relationship with the Oakland community.

McCray, who joined Caltrans in 1959 as a junior clerk, three decades later was in charge of its Disadvantaged Business Enterprise program. During the early 1990s, she led a number of community meetings in Oakland about Caltrans’ plans for rebuilding the collapsed stretch of Interstate 880.

The tone of those meetings often was confrontational, with some longtime Oakland residents holding grudges about how the structure came about in the first place. They felt that Caltrans (then the Division of Highways) had stiff-armed community input in building what was the state’s first double-decker freeway, a 1.6-mile stretch that opened in 1957.

“The community sued the department and stopped (Caltrans’ plans for rebuilding that stretch of Interstate 880), because the route was different from the way it was originally,” McCray, 81, recounted recently. “And the community said, well, we’re not going to let you do it because you didn’t discuss this when it was first built. We were left out. So we’re not going to do this until we are comfortable with what you are going to do.”

Although they played zero role in the Cypress structure’s construction, McCray and her staff were regarded by some Oakland community activists as guilty by association.

“You walk into some of those meetings and you feel like they want to pull your skin off because you work for these people,” is how McCray, 81, described it. She had to keep her cool, though, and strive to somehow lower the room’s temperature so that there would be communication, not combat.

“I’m running the meeting,” she said, “but I also would have the technical people, the engineers who could explain to them why it’s the way it is. You changed it because of this. This happened so we can’t do that. Those kinds of things. So not only do you hold the meetings, you let them ask questions.

"You don’t have a choice about whether you want to tell them or not. It’s their money, so they have a right to know."

“And my piece is, not only would we answer, depending on how egregious or serious it is, you can either get it in writing or we will do another meeting. Whatever. But we want to be sure you understand this is why this is happening. This is not somebody’s whim. This is the requirements. This is what’s necessary.”

As McCray pointed out, money to replace and reroute the collapsed freeway would come largely from the federal government, and part of her job was to ensure that Caltrans complied with all the requirements attached to securing such public funds.

“You don’t have a choice about whether you want to tell them or not,” McCray said in explaining how transparency had to be part of the process, no matter how supercharged the meetings’ atmosphere. “It’s their money, so they have a right to know. …

“One of the things I would tell my staff, you cannot allow (angry activists) to dictate behavior to you,” she continued. “Remember you’re on the clock. We’re supposed to be doing our job. You’re supposed to be doing it the right way. ... You are supposed to keep it together and behave accordingly.”

Where the Cypress structure had stood now lies a boulevard that, at 14th Avenue, features a small park dedicated to the memory of the freeway collapse’s victims. Work to create what is Interstate 880’s current placement to the west of downtown Oakland, closer to the water, was completed in 2001.

Was the Oakland community happy with the results?

“I think overall – because there were several good things that came out of it – that they were pleased,” McCray said. “But there are people, that I’ve experienced, I don’t care what you do and how well you do it, they’re not going to be happy.”

On a nonconfrontational note, one community-outreach effort Caltrans launched in Oakland in 1993 continues to generate positive vibes today. The department-run Cypress Mandela Training Center offers a 16-week pre-apprenticeship course that puts participants on the path to work for organizations such as Caltrans.

“We’re talking huge success,” McCray said. “Amazing. The community’s involved, the unions – I mean everybody.”

McCray, who when she retired in 2003 had attained deputy director status, thoroughly enjoyed her career. “All my education, all my experience, all my exposure, all my everything was with Caltrans,” she said.

All four of her children, one of whom also worked for Caltrans, live near McCray’s longtime home in Sacramento’s Pocket neighborhood– including a daughter across the street. She has five grandchildren and eight great-grandchildren.

“I’m blessed beyond belief,” she said, beaming.