19th Century Kindergarten Uncovered in San Francisco

By Jeff Weiss

A white ceramic mug inscribed with the words, "Merit Awarded," dating back to the 1870s was once held by a child from the backstreets of San Francisco, eagerly awaiting a sip of hot chocolate at the Silver Street Kindergarten, the first free school of its kind west of the Rockies.

Archaeologists from Sonoma State University’s Anthropological Studies Center unearthed the mug while excavating the area near 2nd and Stillman streets in advance of the West Approach Project, an undertaking that rebuilt the concrete freeway connecting Interstate 80 to the Bay Bridge in the early 2000s.

Janet Pape, Caltrans District 4 Senior Archaeologist at the time, since retired, provided oversight for the archaeological and historical study of the area. "The mug recalls a school-day ritual that many pupils would understand today," said Pape. "A mug of hot chocolate was often given to students for their accomplishments."

Janet Pape, Caltrans District 4 Senior Archaeologist at the time, since retired, provided oversight for the archaeological and historical study of the area. "The mug recalls a school-day ritual that many pupils would understand today," said Pape. "A mug of hot chocolate was often given to students for their accomplishments."

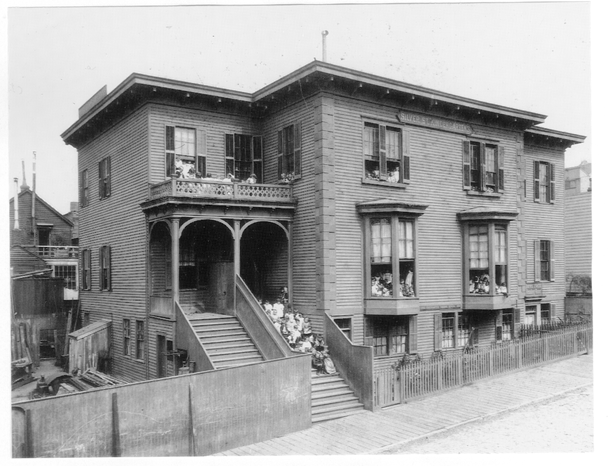

The kindergarten, a large two-story Victorian building, was built in 1878, almost five decades before the first automobile traveled over the Bay Bridge. The building is long gone, burned down by the fire that raged through the city after the 1906 earthquake.

The mug, however, is an artifact that attests to the existence of the school. But how did we get to the place where the mug was discovered and its history revealed?

When Caltrans begins a project, according to Christopher Caputo, Office Chief of Cultural Resource Studies, historical background research quickly follows. Categories might include assessment of the project limits for prehistoric and historic archaeological sites and built environment resources (i.e., historic buildings). Caltrans has many projects of varying size and often the analysis does not reveal the potential for archaeological resources. Other times, especially during large projects that involves extensive digging, a thorough study is required that may include an archaeological investigation.

Unsurprising, the West Approach vicinity was found to have extensive archaeological remains from San Francisco’s historic past just under the modern surface. But even in a city as steeped in history as San Francisco, significant findings aren't guaranteed in all areas; we aren’t, after all, talking about the whole city, but a mere ten blocks. But a cursory evaluation revealed much history in this location, including the kindergarten, which spurred more study and an archaeological dig.

The school was run by Kate Douglas who became famous as one of San Francisco's late 19th Century reformers. She would become famous again, years later, under her married name Kate Douglas Wiggin, the author of the children's classic Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm.

Douglas established the kindergarten on Silver Street, between 2nd and 3rd streets. Silver Street is now named Stillman Street. While the location hasn’t changed, the surroundings have. Most notable is the elevated freeway that runs parallel to the street, nearly overhanging its northern edge.

The property, including the building, was owned by the Crocker family, prominent citizens of the city. Most likely, the building had previously been occupied by an elementary school that had recently relocated several houses down the street. According to the study, "The land, and the building it was in, and the money to support the Silver Street Kindergarten came, in part, from the Crocker railroad fortune, and from well-to-do women from the East, as well as San Francisco."

During the era when the kindergarten opened, education was reserved only for the rich, leaving many children wandering the streets or hanging around their parents' workplaces. The energetic Douglas viewed such childhood idleness as a waste of potential, if not a pathway to an adulthood as a ne'er do well. She hoped the free kindergarten would provide education and structure for the poor children who seemed to turn up on every corner.

An archival photo shows the school bursting with children, many sitting on the front steps, others mugging for the camera from the windows. Looking at it, it's easy to appreciate its social implications and the enormous role it must have played in the neighborhood.

Douglas' teaching methods were popular, too. Before starting the school, she traveled to Los Angeles to learn about the Froebel teaching method, a precursor to the Montessori system that integrates teaching with the principles of play. The system worked well as a means of instruction with the bonus of keeping the children busy.

The Silver Street Kindergarten was such a success that within a year four new free kindergartens had opened in San Francisco. Within 13 years, 66 free kindergartens operated in the city, including those in orphanages, asylums, and day homes.

Such a sudden profusion in a relatively short period might seem astonishing if it weren't for the extended downturn in the economy.

In the 1860s wages were high in San Francisco. The long boat trip around South America was a barrier to population growth and created a chronic labor shortage. But the completion of the transcontinental railroad 1869 opened a relatively quick overland link, increasing the labor pool.

In 1873, the Jay Cooke Company, a major financier of a second transcontinental railroad route, closed its doors, sparking the Financial Panic of 1873. Soon, the poor and unemployed from the east coast boarded railway cars heading to San Francisco in pursuit of opportunities that didn't exist.

In 1873, the Jay Cooke Company, a major financier of a second transcontinental railroad route, closed its doors, sparking the Financial Panic of 1873. Soon, the poor and unemployed from the east coast boarded railway cars heading to San Francisco in pursuit of opportunities that didn't exist.

The result was that unemployment ran rampant from the 1870s until the turn of the century. Many of those with jobs fared little better. Over 20 years, beginning in the mid-1870s, wages dropped from $20 to $2 a day, creating an enormous class of working poor.

The poverty-stricken parents were undoubtedly pleased with the free education their children were receiving, but the school provided more than that. "[The parents] also loved it because the school fed their children at a time when money was scarce, " said Pape.

"The school and its teaching methods became so popular that educators came to San Francisco to study the teaching methods," said Pape. Indeed, the Silver Street Kindergarten became so popular that, at times, visiting teachers outnumbered the students.

Douglas, however, didn’t see this as a problem as she was an avid educator of the educators themselves. By teaching her visitors the nuts and bolts of her system, she helped expand the free-kindergarten system and gave more children the tools to break out of poverty.

In 1880, Douglas recruited and trained her sister, Helen Archibald Smith, to become the school principal while she concentrated on training new teachers and writing articles. The following year she married her childhood sweetheart, Samuel B. Wiggin. The couple moved to New York in 1884 where Kate Douglas Wiggin earned fame and fortune by writing Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm and other articles and stories. The kindergarten continued to operate successfully under her sister's care.

The "dig" also uncovered information about the buildings and residents occupying the Rincon Hill area in the late 19th century. Upper-middle-class residents tended to live in homes along the larger thoroughfares, while houses on the side streets were homes to the working class. The historical team collected remarkably detailed information including names, addresses, and vocations of the residents. While it's a colorful and precise historical snapshot of the era, the most notable findings clearly relate to the Silver Street Kindergarten.

Email: jeffrey.weiss@dot.ca.gov